History of Translation (and Interpretation)

It’s often said that translation is like a bridge.

And like real bridges, it has developed a lot throughout history whilst still serving the same essential function.

From discussions between tribal peoples to UN summits, translation and interpretation (spoken translation) have been bridging human societies since the dawn of time.

By better understanding the history of translation, we can better appreciate how far it has come.

In this article, we will give a brief overview of the history of both translation and interpretation.

What is translation?

Translation is simply when the meaning of text in one language is written into text in another language.

This can be done by a human or a machine. The former might be a professional translator or anyone who knows a bit of another language.

When it is done professionally, the language being translated from is often called the source language, and the language being translated into is called the target language.

(Of course, this is how it’s referred to in English – other languages have their equivalent translation of these terms!).

Outside of the translation industry, translation is often confused with interpretation (see below).

What is interpretation?

Interpretation is an oral translation from one language to another.

In the translation industry, it is divided into two main types: consecutive interpretation and simultaneous interpretation.

Consecutive interpretation is when the interpreter listens to the speaker and then – when the speaker stops speaking – repeats what the speaker said in another language.

Simultaneous interpretation is when the interpreter says what the speaker is saying almost in real-time, i.e., as the speaker is speaking. This difficult task is usually done by using soundproof booths, headsets and microphones.

What is the difference between translation and interpretation?

The difference between translation and interpretation is that translation is for written communication whereas interpretation is for spoken communication.

However, both of these skills have been interconnected throughout history. To describe the history of one without the other would lead to an incomplete article.

So, now that you know the difference between the two, let’s take a closer look at their fascinating and unique histories…

A brief history of translation and interpretation

1. Interpretation in pre-history…

Before written communication was created, interpretation was the only bridge between languages.

Today, in places like the Amazon rainforest and the highlands of New Guinea, we can still glimpse how mankind lived before ancient civilisations appeared.

When Jared Diamond travelled to New Guinea, he was surprised to see how multi-lingual most people were. One night at a campfire he questioned them about this:

Among those New Guinean, the smallest amount of languages anyone spoke was 5. Several men spoke from 8 to 12 languages, and the champion was a man who spoke 15.

– The World Before Yesterday (2012)

Napoleon Changnon was similarly impressed with the skills of the Yanomamo people of the Amazon:

While it is true that the number of words in the English vocabulary greatly exceeds the number in the Yanomamo vocabulary, it is also true that we know fewer of them than they do of theirs. If you do not have a written language, you have to store more in your head.

– Yanomamö: The Fierce People (1967)

Daniel Everett is another well-known anthropologist. He lived with the Pirahā people in the heart of the Amazon for over 30 years. He found learning their language an intriguing challenge.

Pirahā is not known to be related to any other living human language […]. It sounded like nothing I had ever heard before. The language, it seemed, was intractable.

Becoming fluent profoundly changed his thinking. But he found that the basic issues of translation remained:

Talking to people from very different cultures […] involves much more than merely getting the word meanings right. One can translate every word well and still have a hard time understanding the story. This is because our stories include unstated assumptions about the world that are made by our culture.

– Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle (2010)

In these societies, villages are often just a few miles apart. But they frequently have their own dialect or language. So, being able to speak multiple languages is essential. In other words, many people end up being interpreters!

Today, some of these remaining languages have been recorded, transcribed and translated by anthropologists. Sadly, many others are lost forever.

2. Translation in the ancient world

The earliest known ancient civilisation is Sumer, which was in Mesopotamia (located in the modern-day Middle East).

The oldest known dictionary in history is a bilingual Sumerian and Akkadian dictionary dating from around the year 2300 BC. It is made up of 24 stone tablets listing the names of various items, such as stones, plants, animals and stars.

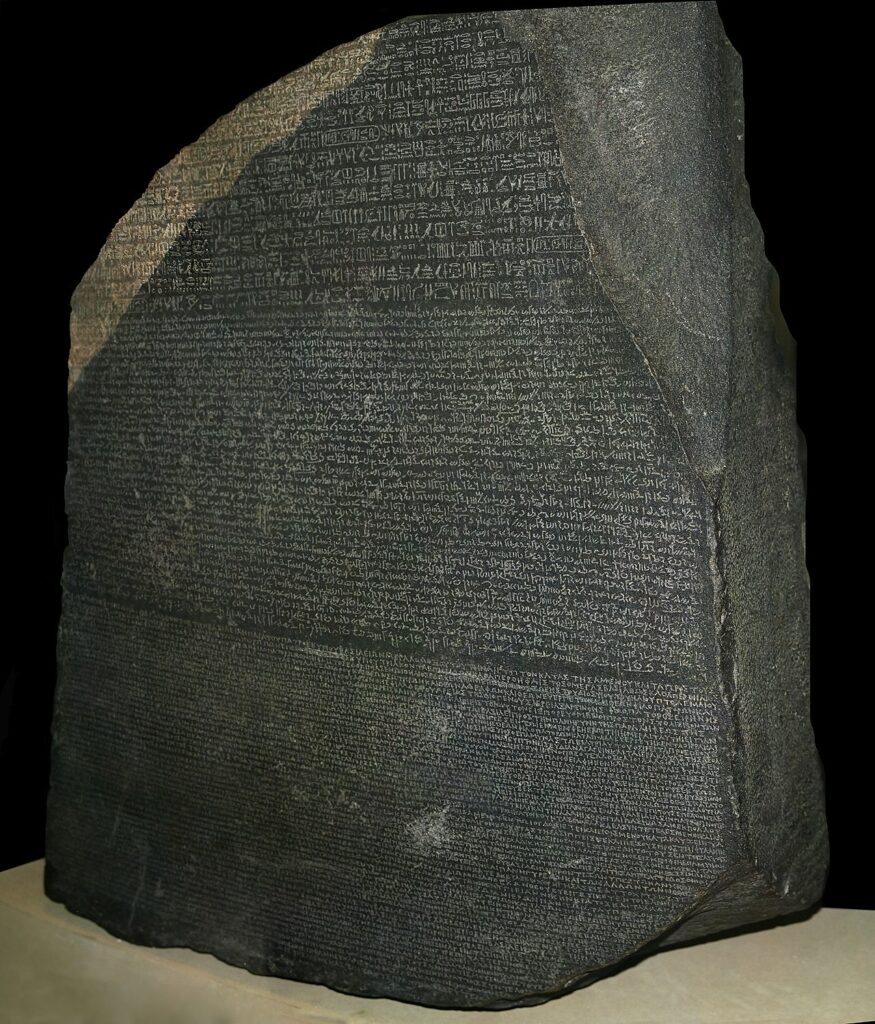

Mesopotamian writing is said to have inspired the famous Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph system, which dates back to about 3300 BC.

In 1799, a French officer found the Rosetta Stone, which had two different forms of Ancient Egyptian written besides Ancient Greek. This translation of a religious decree was the key to understanding Ancient Egyptian.

The role of lingua franca in the ancient world

A lingua franca is a common language used by groups who do not share the same native language.

In the ancient world, lingua francas not only helped people from different kingdoms and empires speak but also helped people within kingdoms or empires speak.

Today, it can be argued that English is the world’s lingua franca, especially for commerce and governmental matters.

Lingua francas saved – and continue to save – people from having to translate between large numbers of different languages and dialects.

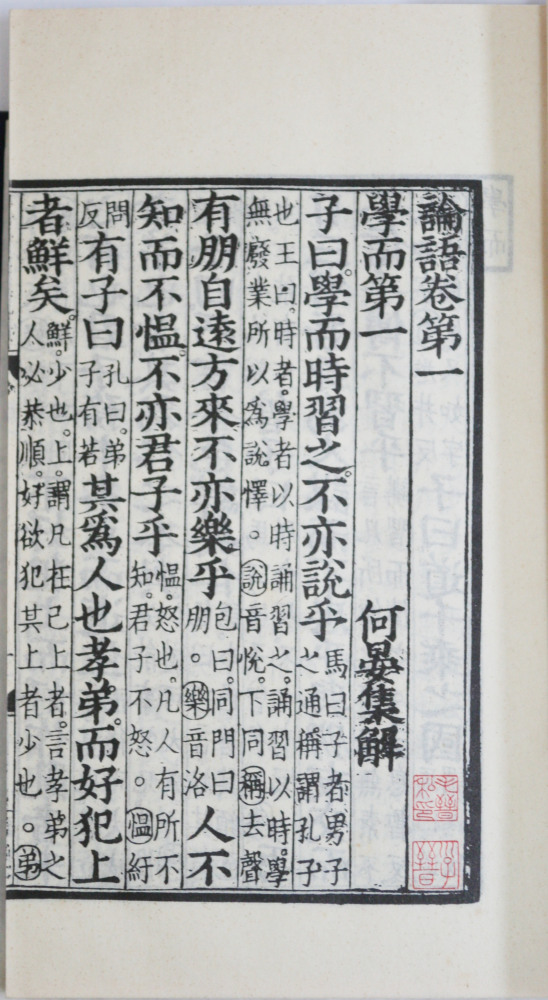

Lingua Franca Example 1: Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese has a history stretching back millennia. In the Analects, it is noted that Confucius would carefully observe when he used ‘the correct pronunciation’:

Occasions when the Master did not use dialect: when reciting Classical poems and documents, and when performing ceremonies. On all these occasions, he used the correct pronunciation.

– Analects

It remained the lingua franca of non-Chinese elites in East Asia for a long time, too. So, for example, when the Mongol Emperor Kublai Khan (1215 – 1294) began sending letters to the Japanese in 1266 to request they submit to his empire, he used Classical Chinese.

The Japanese could read the letters perfectly well. However, they chose to ignore them. Then Kublai sent more threatening letters. So, to make their answer clearer, in 1280, the Japanese executed the emissaries sent to them.

Kublai gave up writing to them not long after…

A few centuries later, in 1488, the Korean official Ch’oe Pu’s ship was blown to China by a storm. He was able to communicate with the Chinese by writing Classical Chinese.

This ability no doubt saved his and his crew’s lives, as he was able to use the language to persuade those he met that he was not a Japanese pirate (for which the punishment would have been execution).

Historian Timothy Brook explains further:

Many were puzzled to discover that Ch’oe could not speak Chinese but could read it. ‘Why’, one local scholar asked at one of the inns where he and his companions were put up, ‘when your books have the same writing as those of China, is your speech not the same?’ […]

– Timothy Brook, The Great State (2019)

[Ch’oe answered:] ‘If you wonder at the sound of my words, I wonder at yours. It is simply a matter of custom.’

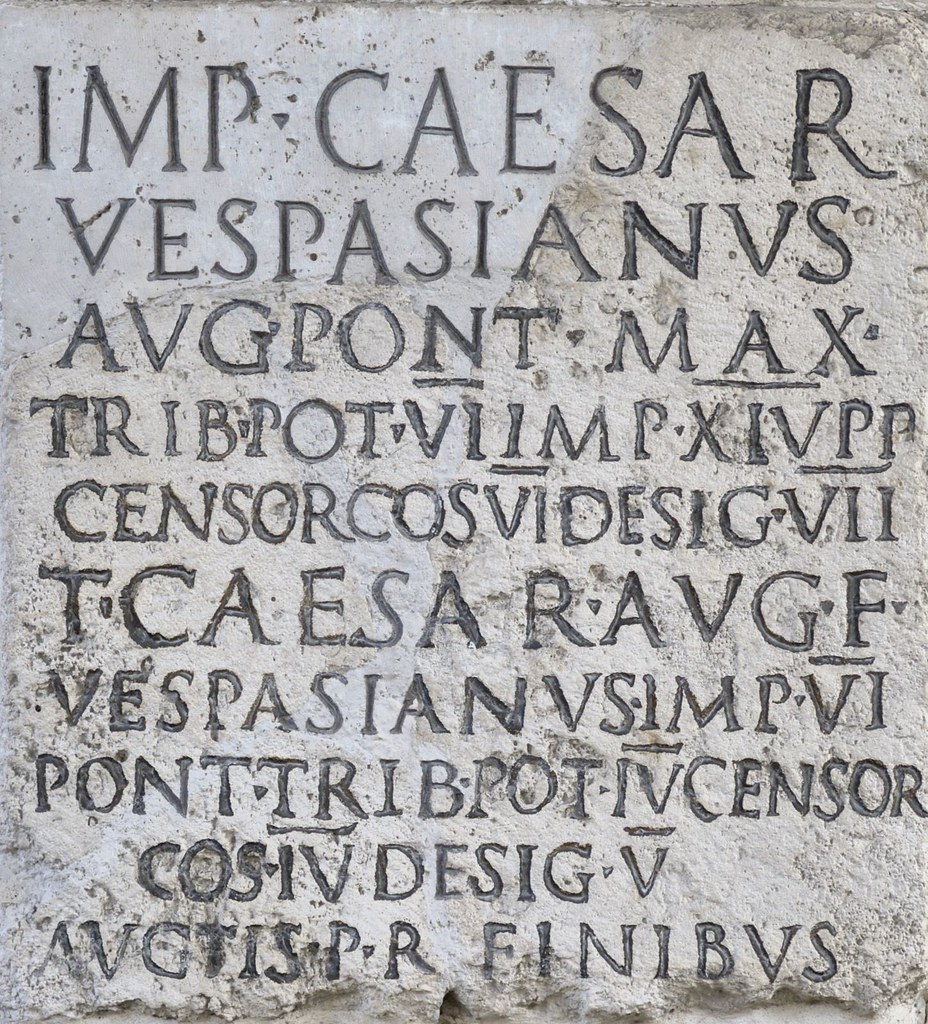

Lingua Franca Example 2: Latin

At its height in 117AD, the Roman Empire covered 5 million square kilometres, from the North of England to the Persian Gulf.

Latin originated in central Italy and soon spread across new lands with the empire. It wasn’t just spoken by Roman soldiers though.

It helped create the many Latin languages we still see across Europe today. And it was the lingua franca of educated elites across Europe right until the 18th century. It’s estimated that about 29% of the English language comes from Latin.

It was used during the early days of contact between European and Asian powers (see below, ‘The Treaty of Nerchinsk’).

And even Oliver Cromwell (1599 – 1658), a relatively un-scholarly man, was able to use Latin to converse with ambassadors.

3. Translation in the medieval era (approximately 500 – 1499)

The first two-thirds of this period is often called ‘the dark ages’, a term first coined in the 1300s. However, some scholars believe that this is a misleading title.

Either way, trade, travel and conquest brought about the rise of many different civilisations and their written languages before and during this period.

Who were the early translators?

Translation is an old profession. It is likely that in the ancient and medieval world, most translators and interpreters worked in religious and governmental roles. Back then, both of these were deeply intertwined.

They were often used to communicate in matters of warfare, trade, politics and tax collection. The latter category would be necessary because many empires and kingdoms would have had more than one language.

The Venerable Bede (673 – 735)

Bede was an influential scholar, historian and translator. He was an English monk living in a monastery in the northeast of England.

He was the first person to translate sections of the Bible into Old English. And his editing of the Latin translation of the Bible remained the Vatican’s preferred version right until the 20th Century.

Marsilio Ficino (1433 – 1499)

Marsilio Ficino was a priest living in the Republic of Florence. He was one of the most influential scholars of the Renaissance thanks to his translation of the complete works of Plato into Latin.

His translation helped Europe re-discover Greek texts that inspired generations of political and philosophical thought.

4. Translation in the Early Modern period (approximately 1500 – 1700)

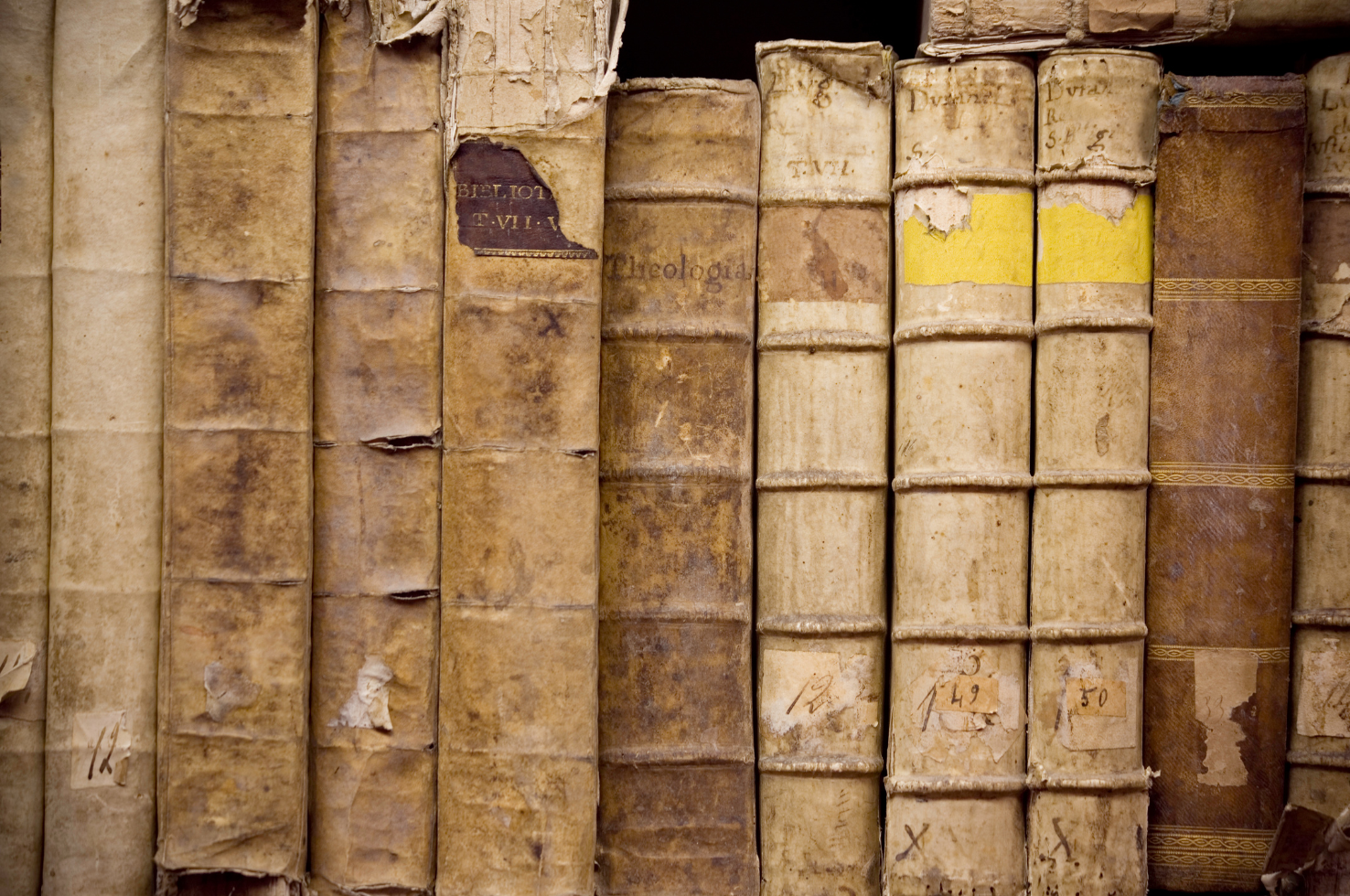

The early modern period overlaps with the invention of the printing press, the Renaissance, the Reformation, the Age of Discovery, and more.

During this period, globalisation grew rapidly. Columbus had just crossed the Atlantic in 1492 and Magellan first circumnavigated the world between 1519 and 1522.

Exploration, trade, and empire-building caused many different civilisations and languages to come into contact. We are no longer talking about the occasional translation being handwritten by religious scholars.

The explosion in translation that occurred during this period would take a very thick book to summarise. So let’s just take a glimpse at some highlights from around the world.

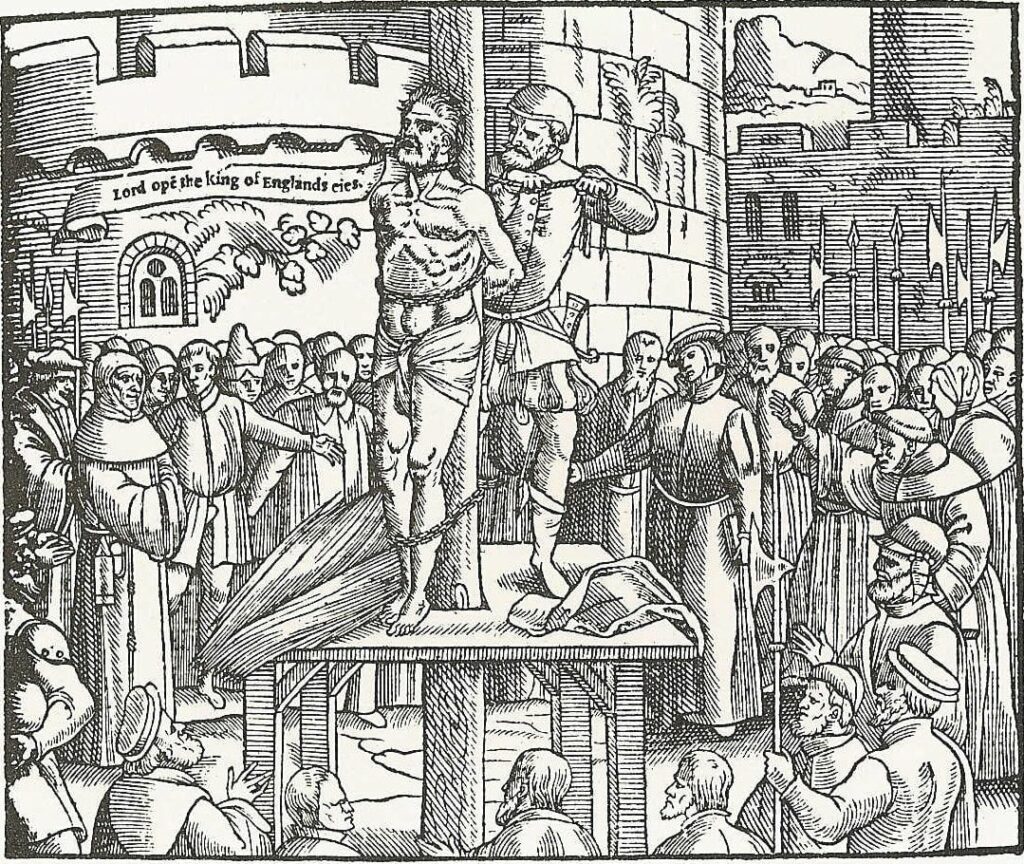

William Tyndale (1494 – 1536)

William Tyndale is seen by many as perhaps the most influential figure on the English language.

Tyndale’s translation of the bible into English was the most complete up until that point. It heavily influenced the King James Bible, which came a century later.

It’s argued that perhaps up to 93% of the King James Bible’s New Testament, for example, was based on Tyndale’s version.

Tyndale translated directly from Latin, ancient Greek and even Hebrew. Unfortunately, his work angered ‘the powers that be‘ (a phrase he coined) in England, especially Henry VIII and Thomas More.

He fled to Antwerp in Belgium but was eventually caught and executed by the Holy Roman Empire.

During his lifetime, many of Tyndale’s translations of the bible were burned. And on occasion, so too were people who were caught with them.

However, just a few years after his death, Henry VIII commissioned four translations of the Bible, all heavily based on Tyndale’s work.

Anjirō (1511 – 1550): Japanese interpreter for Francis Xavier (1506–1552)

Trade and religion often went hand in hand during this period of history. About 6 years after the Portuguese first made contact with Japan in 1543, the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier travelled there.

In 1545, on the Malay Peninsula, he met Anjirō, a former samurai who had escaped his home country after murdering a man.

Anjirō would become the first-ever Japanese Christian and with the Portuguese that he had learned, the first interpreter between a European language and Japanese.

Xavier spent more than two years in Japan trying to spread Christianity. Unfortunately, a theological disagreement eventually caused Xavier to drop Anjirō as his interpreter.

The latter had translated the term for God as Dainichi (a cosmic Buddha) rather than Deuso (from the Portuguese Deus). However, some modern scholars have argued that Anjirō’s choice was likely the most appropriate for its time and circumstances.

John Milton (1608 – 1674): Secretary For Foreign Tongues for the British Interregnum (1649 – 1660)

After years of civil war in Britain, King Charles I was executed in 1649. The next 11 years, before King Charles II was made king, are now known as the Interregnum.

Throughout the Interregnum, the poet John Milton held the role of Secretary for Foreign Tongues. Besides writing defences and correspondence of the new republican regime (in Latin and other languages), his job also involved translation.

What makes his work during this period (and after, when he wrote his masterpiece Paradise Lost) particularly impressive, is that he went blind in 1652. He would use assistants to read documents to him and transcribe his work.

Milton would go on translating until his death in 1674. One of his last works was a translation of a treatise in favour of elective monarchies.

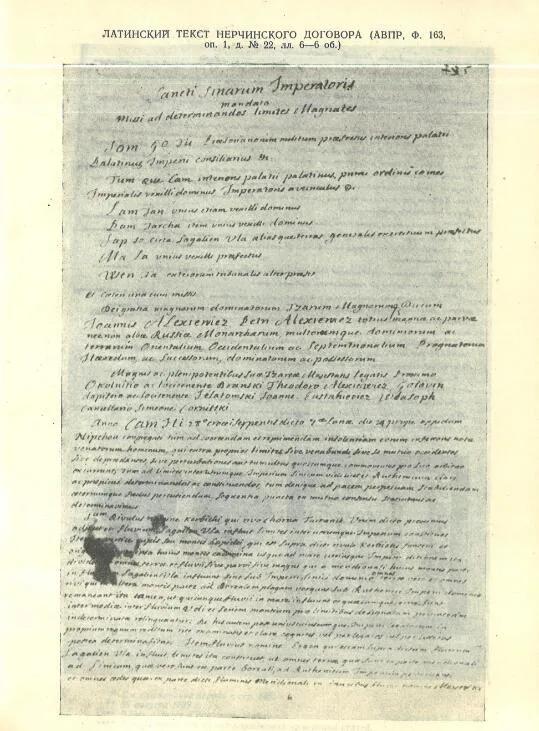

The Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689)

The borders of the Russian and Chinese(/Manchu) empires increasingly came into contact in the 17th century.

In 1618, for example, a Russian diplomatic mission reached Beijing. It was turned away and the diplomats were given a letter from the Chinese Emperor (Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty) inviting them to present tribute.

Unfortunately, no one was able to translate this letter until 1675…

In 1689, with a new Dynasty in charge of China (the Manchu Qing Dynasty), the leaders of each empire agreed to meet in Nerchinsk in Russia’s far east.

Unfamiliar with one another, they had to rely on jesuit translators (/interpreters) from Poland, France and Portugal to help them negotiate and write their treatise:

On the first day of the meeting, August 22, the envoys agreed in principle to communicate in Latin… they believed that there were not enough Mongolian translators, and these were not reliable, so both sides agreed that it would be more “objective” to rely on the Jesuits’ Latin…. [the Russians soon] realized the Jesuits were “inserting words” in their translations…

– Peter C. Purdue, China Marches West (2005)

…Mongolian could certainly have served as a better bridging language just as easily as Latin; by excluding it, the Jesuits put themselves in the position to get better terms for the propagation of their religion from both sides.

The final treaty lasted nearly two centuries.

5. Translation in the Age of Revolution (1765 – 1849)

The period between 1765 and 1849 saw the expansion of multiple empires and even faster globalisation.

The Austro-Hungarian, Manchu, British and Russian empires all reached their peak in size during this time, for example.

It was also a time when lingua francas spread across the globe. This had the unfortunate consequence of destroying, or nearly destroying, many smaller languages.

For example, in the British Isles alone, the last native Cornish speaker is believed to have been Dolly Pentreath (1692 – 1777).

And going into this period, Irish was the majority language of Ireland with over 800,000 speakers, but by the end of it, this number was down to 320,000.

George Staunton (1781 – 1859): English and Chinese translator and interpreter

George Thomas Staunton was the son of the British diplomat George Leonard Staunton.

Before setting off to China, the Stauntons travelled across Europe in search of a Chinese language tutor for the young George.

By the time they reached China in 1792, his Chinese was good enough to enable him to act as an interpreter for Lord McCartney on his famous unsuccessful mission to meet the Emperor Qianlong. McCartney remarked in one letter:

Little George Staunton has long since learned to speak [Chinese] and write it with great readiness, and from that circumstance has been of infinite use to us on many occasions.

The elder Staunton passed away in 1801, but his son stayed on in China until 1816.

He went on to translate many texts between Chinese and English, including putting the Chinese penal code into English. He also advised other well-known translators, such as Robert Morrison and Thomas Manning.

German translations of Shakespeare

Germany can confidently claim to be Shakespeare’s number-one fan nation outside of Britain. It was the first country to translate Bard’s complete works between 1762 – 66, and it founded the first Shakespeare Society (die Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft) in 1862.

There have been many different translations of Shakespeare’s works since then. However, translations of his words have still managed to enter the German language. Here are just three examples:

- Was ist ein Name? (what’s in a name?)

- Viel Lärm um nichts (much ado about nothing)

- Der Anfang vom Ende (the beginning of the end)

And today, the Stratford-upon-Avon playwright’s words are still enjoyed in German all across the nation. It’s claimed that there are more performances of his plays in Germany than in England.

6. Translation in the mid to late 19th and early 20th centuries (1850 – 1950)

The late 19th century and early 20th century saw the industrial revolution spread around the world. It also saw increased standardisation of many languages and a large rise in literacy.

It’s also a time when we can see translation services begin to evolve and standardise.

The growth of commercial translation services

International trade thrived during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Shipping times were sped up considerably by engineering of transport and passenger liner ships: in the early 19th century it took about 6 weeks to cross the Atlantic, by the end of the century it took just 8 – 9 days, and by the 1950s it was down to 4 days.

This meant that there was more opportunity for translation and translators around the world.

One example of this was the American businessman Carl Crow, who worked in Shanghai during the 1920s and 30s. The city was then the commercial center of east Asia and was known by many as ‘The Paris of the East’.

In his famous memoir, Crow details how he and his translation team struggled to come up with terms during their work:

The translation of poker was the most difficult job of that sort we ever undertook, but when we began advertising motor-cars, we found plenty of trouble expressing terms in the Chinese language.

– Carl Crow, Four Hundred Million Customers (1937)

The Nuremberg Trials, 1945: The invention of simultaneous interpretation

After World War II, the allies jointly put the Nazi leadership on trial. Up until this point, it had been standard practice to use consecutive interpreters in courtrooms when needed.

However, this trial required English, French, German and Russian interpretation. Colonel Léon Dostert, a French-born linguist based in the US came up with the the concept of simultaneous interpretation using headsets and microphones.

The trials also laid the foundation for modern international criminal law. Without simultaneous interpretation, proceedings could not have progressed as efficiently and accurately as they did.

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL)

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL) is a professional body which promotes the study and practice of linguistics.

It was founded in 1947 as the Association of Language Teachers and became the Chartered Institute of Linguists in 1979.

The CIOL provides qualifications in linguistics and runs events and training courses to help linguists keep up to date with the latest developments in their field.

7. Translation in the second half of the 20th century (1951 – 1999)

The latter half of the 20th century saw the rapid evolution of professional translation services across the globe.

The world’s population grew from 2.5 to 6.1 billion during this period, and technology replicated itself just as quickly.

This period saw the rise in translation services being dominated by professionals. They increasingly came to specialize in certain languages or fields, such as medical translation or legal translation.

Language competency alone no was no longer enough. They must have an excellent command of both languages, strong research skills and cultural awareness.

Translation studies appear (late 1954)

Translation studies began as an academic discipline in the early 1950s.

The discipline was founded by a group of scholars who were interested in exploring the different methods and translation theory. The first translation studies department was established at the University of Vienna in 1954.

The objective of translation studies is to explore the theory and practice of translation and to help translators and interpreters improve their skills.

Although not all translators have attended translation studies courses, many have begun bringing their knowledge over into the commercial world.

The first machine translation (1954)

The first machine translation was created in 1954 by a group of scholars at the University of Vienna. They worked with IBM to automatically translate 6 sentences between Russian and English at the IBM HQ in New York.

The purpose of machine translation was to help translators and interpreters improve their skills. It has come a long way since then.

Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) tools are now commonplace across the translation industry. And great strides are being made in the field of AI translation (see below, ‘The future of translation’).

American Translation Association (ATA) is founded (1957)

The American Translation Association (ATA) is a professional association for translators and interpreters which provides resources and support to its members.

It was founded in 1957 and offers certification exams, directories of translators and interpreters, and a variety of other useful resources and training.

It also keeps members up to date with the latest developments in their field.

North Korean kidnappings of Japanese civilians (1977 – 1983)

Between 1977 and 1983, the North Korean government kidnapped at least 17 Japanese civilians from Japan’s eastern coast.

The true figure may be much higher but remains unknown because of the lack of evidence and cooperation of the North Koreans. Only five have ever returned to Japan.

The victims were generally young people in their twenties or younger. One of them, Megumi Yokota, was only 13 when she disappeared walking home from school in her seaside village.

It is widely believed that one of the primary motivations for the kidnappings was to gain native speakers of Japanese to train North Korean spies and translators.

Bizarrely, some were even given jobs translating from Japanese into Korean – something any number of North Koreans who spoke Japanese could have done themselves.

The Digital Revolution

The Digital Revolution (sometimes called the Third Industrial Revolution) is the name for the period during the late 20th century when technology switched from analogue to digital.

It was during this time we saw the widespread use of desktop computers (in the 1980s) and the internet (1990s). Both of these significantly transformed how the translation process was carried out.

Each translator could now increase their capacity for work simply by using simple processing software such as Microsoft Word.

And specialised roles such as translation project managers were made more efficient by the ability to communicate with translators, proofreaders and customers via email.

Widespread use of translation memory tools and machine translation services also helped automate previously time-consuming tasks.

In short, the digital revolution enabled translation services to translate more and provide better translation quality assurance than ever before.

8. Translation in the early 21st century (2000 – present)

Since the year 2000, the translation industry has continued to grow and evolve significantly.

The most notable difference is the increasing demand for interpreters in addition to translators.

In the late 20th century, interpretation was not as widely used as it is today, and translators typically handled both translation and interpretation tasks.

However, due to the globalization of business, there is now a greater need for people who are specialized in interpretation.

Additionally, the use of technology has continued to have a significant impact on the translation industry.

In particular, the growth of online translation tools has continued to make it easier for both customers and translators to translate documents quickly and accurately.

This enables translators to manage a higher volume of work with greater accuracy than ever before.

The profitability of translation services industry is currently kept in check by the ability of translators to adapt to this new technology and to offer other services, such as localization and transcreation.

The future of translation?

As with many industries, the precise future of translation is uncertain. But what is certain is that big changes are likely to take place.

Many believe that the growth of AI means that machine translation might replace human translators perhaps within even the next 5 – 10 years.

Others are more optimistic and think that translation services will co-opt the technology to increase their efficiency whilst developing their localization and transcreation offerings.

Interpretation, too, could well be replaced by machines. Meta (formerly Facebook) is just one example of a company working on developing real-time machine interpretation.

Others argue that the human touch of real-life interpretation means that human interpreters won’t go out of business any time soon.

Conclusion

Before large-scale civilisations appeared, tribal groups often had to use their own language skills or interpreters to communicate with other groups. Today, we can still glimpse this way of life in parts of the Amazon, Papua New Guinea and elsewhere.

The written translation appeared soon after the world’s first written texts were created in the ancient world. The earliest examples are from Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

In the ancient world, scholars working on religious texts and translations of government decrees appeared around the world. One of the first examples in English is the monk Bede, who helped improve translations of the Latin bible.

The use of lingua franca around the world helped many elites avoid the need for translation services some of the time. However, as exploration, trade, and conquest brought more people into contact, translators were in increasing demand.

In the Early Modern period (approximately 1500 – 1700), religious translation still dominated to an extent. This was especially true in the European languages, as the continent underwent the Reformation started by Martin Luther.

However, increasing contact between the Western world and other civilisations also meant that Asian languages began to be translated. Anjirō was both the first Japanese Christian and interpreter between a European language and Japanese.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, global travel and trade grew even faster than ever before, and the demand for commercial translation services grew rapidly.

By the middle of the 20th century, new linguistic organisations and translation studies courses appeared. These helped bring standardization to an increasingly professional and specialised industry.

Advances in machine translation and the digital revolution further transformed translation services. The translation process became faster and more accurate than ever before.

Today’s modern world requires accurate translations from one language to another for global business operations, conferences, tourism and education.

Translation continues to be an important part of our global community and plays a vital role in communication and understanding.

It forms the very bridges that millions if not billions of people must cross every day.